Bibracte is a short-lived town, which only lived for a century, between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. A century which separates its foundation from its abandonment in favour of Augustodunum (Autun).

Bibracte's golden age

Une ville éphémère

Capital of the Aedui people, it had between 5,000 and 10,000 inhabitants, was a hub for crafts and trade, saw the proclamation of Vercingetorix at the head of the Gallic coalition in the summer of 52 B.C. and the installation, for one winter, of Julius Caesar, who wrote part of his Commentaries on the Gallic War there.

Bibracte was the site of and witness to a radical transformation of Western European societies, with the appearance of oppida, these walled towns, of which Bibracte is one of the most characteristic and best preserved, with its double ramparts and its districts extending over 200 hectares.

One of the main achievements of 19th century archaeological research is to have shown that the Gallic town was an important craft centre, especially the area behind the Rebout Gate. Here, in workshops, several generations of craftsmen shaped iron and copper alloys to make thousands of fibulae, tools, weapons, coins and enamelled metal ornaments, which were traded on the regional market and even beyond.

Bibracte was also an important commercial centre, as shown by the coins, both local and distant, found on the site. It was a crossroads where imported goods and handicrafts were exchanged and consumed.

It was also a political capital, described by Caesar as "the largest and richest oppidum of the Aedui". In the summer of 52 BC, it hosted the assembly of Gallic chiefs that confirmed Vercingetorix's command, before being chosen a few months later by Caesar to set up his winter quarters there, after his victory at Alesia.

Sleeping Bibracte

The abandoned town

After the departure of its inhabitants for the town of Autun, in the decades surrounding the change of era, Bibracte did not quite die. But it did fall asleep.

All that remained on Mount Beuvray were a few places of worship and springs that continued to be used. The dwellings, without disappearing completely, are very scattered.

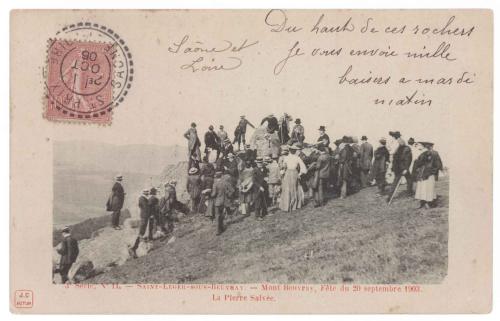

After the poorly documented centuries of the early Middle Ages, Mont Beuvray reappears in texts as the site of fairs held on the first Wednesday in May. These fairs, which lasted until the First World War, are still alive in the local memory.

At the beginning of the 15th century, a Franciscan monastery was established below the summit and welcomed about fifteen monks. This establishment remained until the beginning of the 18th century, despite two destructions during the Wars of Religion.

The rediscovery

In the 19th century came the time of the archaeologists...

It was a time of rediscovery that was driven by political concerns and the historiographical myths of the time.

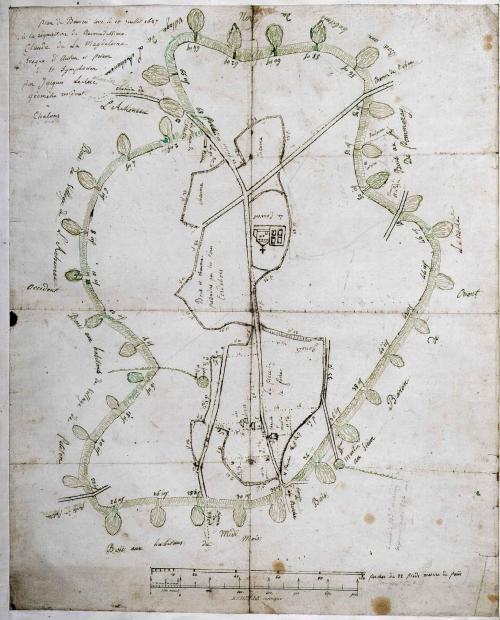

It all began when Napoleon III decided to write A History of Julius Caesar. He then commissioned research to determine the location of Alesia and Gergovia and financed vast programmes of archaeological excavations. A wine merchant from Autun, Jacques-Gabriel Bulliot, who was very erudite, was convinced that Bibracte was located on Mount Beuvray, and not in Autun, as was thought at the time. In 1867, he received financial support from Napoleon III and set up excavation campaigns that he supervised for nearly 30 years.

These excavations, which he documented with precision in field notebooks, made it possible to uncover houses, workshops and public buildings, and to collect thousands of objects or fragments, which were distributed between the Autun Museum and the National Antiquities Museum in St-Germain-en-Laye.

Bulliot then left the direction of the research to his nephew, Joseph Déchelette. A great traveller, it was he who established that certain objects discovered at Bibracte were identical to others found in Bavaria, Hungary or Bohemia and who demonstrated that there was a "civilisation of oppida", which extended over a vast part of Europe. Considered one of the fathers of protohistoric archaeology, he wrote a monumental manual of European archaeology. His death on the front line of the First World War in 1914 brought research at Bibracte to a halt.

Despite the departure of the archaeologists, Mount Beuvray remained a place for Sunday walks, festivals and agricultural fairs for the local population.

Today

An archaeological site that reveals itself

Today, Bibracte is a place where researchers, excavators, tourists and walkers meet. The site of an ancestral heritage that bears witness to an important page in European history, it is also one of the most dynamic archaeological sites of this century, resolutely turned towards the future.

When Déchelette died on the front in 1914, archaeological research on Mount Beuvray came to an end, until 1984 when, on the initiative of archaeologists, supported by the President of the Republic François Mitterrand, it was resumed. The site has been excavated every year since then.

Only 5% of the site has been excavated to date. There is still a lot to be done, either directly in the field or through the use of new technologies, to get a detailed view of the functioning of the ancient city. This is what the university teams present every summer are working on, both on the excavations and in the workrooms of the archaeological centre.

And, if its winters remain calm, the site is animated in summer by a crowd of visitors, who come to seek on this Mount Beuvray, Grand Site de France, the pure air, the walks in the middle of the hundred-year-old beeches, the memory of the ancient city and a moment of History.

Each season, a rich and varied programme of cultural activities enlivens the site with guided tours, workshops, concerts, conferences and artists' proposals. The museum, which welcomes nearly 50,000 visitors a year, makes Bibracte a cultural centre that cannot be ignored in Burgundy.